Introduction

Worldwide issues in economic, social, health, and environmental terms

The COVID19 pandemic has created an atmosphere of uncertainty for humanity due to its effects on economic, social, health, and political areas. In the first months of 2020, a new coronavirus became a global issue, declared a global health emergency by the World Health Organization (WHO) in March of that year. As a result, a portion of the global population had to integrate new rules for movement restriction into their daily routines, and a preventive confinement measure was implemented through the closure of non-essential businesses (Williams and Kayaoglu, 2020). In this complex scenario, political, social, economic, and health problems converge, which are part of the current environment of global society.

In response to this, nations around the world have implemented a series of public policy measures aimed at containing the spread of the virus and mitigating the economic and social impact through fiscal and monetary stimulus, as well as measures to protect the most vulnerable. Public health measures have been successful in reducing the number of deaths during the early months of the pandemic, but some measures have generated high uncertainty and fear of infection risk, leading to economic contraction and job losses (OECD, 2020) due to either imposed or voluntary confinement. This has caused a spiral of events that have led to a set of problems for society in various dimensions. In this environment, while some countries started with relaxed restrictions and have gradually increased activities, others continue to struggle with the most critical phases of the pandemic, including a second wave of infections (SRE and Instituto Matías Romero, 2021).

Therefore, the immediate priority for most nations is access to basic services: healthcare, clean water and sanitation, as well as education. In this scenario, the next priority is to promote international solidarity and increase global support for regions where the pandemic has had the greatest impact (including poverty, inequality, and access to job opportunities) (UN, 2020). This simultaneous and multidimensional crisis has been a starting point for strengthening the idea of a better economic, political, and social system focused on the comprehensive well-being of people.

The COVID19 pandemic has created an atmosphere of uncertainty for humanity due to its effects on economic, social, health, and political realms. The world has implemented a series of public policy measures aimed at containing the spread of the virus and mitigating the economic and social impact through fiscal and monetary stimuli, as well as measures to protect the most vulnerable. However, measures such as confinement have generated high uncertainty and fear, causing economic contraction and job losses. The immediate priority for most nations is access to basic services such as healthcare, clean water, and sanitation, as well as education. The next priority is to promote international solidarity and increase global support for regions where the pandemic has had a greater impact, including poverty, inequality, and access to employment opportunities. This multidimensional crisis has been a starting point for strengthening the idea of a better economic, political, and social system focused on the well-being of people as a whole. The COVID19 crisis was a global and simultaneous event that has affected the way people work, study, and carry out their social activities, infecting more than 167 million people and caused over 3.48 million deaths worldwide. In Mexico, the total number of cases reported as of May 2021 was 2.4 million, with a total of 222,000 deaths reported, making this disease one of the leading causes of both direct and indirect deaths (not related to the disease but to the availability of hospital resources) in the country. In terms of impact on the population, people in poverty have been the most affected, from job loss to vulnerability to contagion, and lack of access to healthcare and social protection services. This situation in Mexico has been studied, with workers in manual and operational jobs, homemakers, and retirees and pensioners accounting for 94% of deaths. COVID-19 and the associated economic crisis represent relevant factors in projections of poverty in the world, with estimates indicating that between 88 to 115 million people have fallen into extreme poverty as a result of the pandemic, with levels of poverty possibly reaching 150 million in 2021 (World Bank, 2020). Therefore, it is necessary to consider creative solutions to improve not only the economic environment but also social interaction and access to health services.

In addition to what has been said, the labor dimension has suffered a severe impact, with an emphasis on sectors with lower incomes and a higher degree of exposure due to the nature of their productive activities based on direct interaction among people. According to the International Labour Organization (ILO), estimated working hours in 2020 were 10.5% lower compared to 2019 (equivalent to 305 million full-time workers). Additionally, around 436 million businesses have been affected by pandemic containment measures, while the global relative poverty rate increased by about 34% for informal workers (ILO, 2020). Therefore, direct support for both formal and informal workers, as well as small and medium-sized enterprises, should be considered the priority focus of economic and labor recovery plans.

It can be said that the pandemic showed to a large extent a reality that the world refused to see, since it could be observed that adaptation to the market and to the world itself without access to any type of digital tool made the difference between surviving and dying. Much of this is due to the fact that this unusual phenomenon deeply affected most countries in the world, since it has represented a major rethinking of social practices and production systems that until recently were considered normal. The world economy contracted by 3.1% in 2020, and despite the recovery that began in 2021, many economic and social effects still persist (Monetary Authority of Singapore, 2021).

One of the most evident events, where it was possible to observe the marked difference between having digital media was perhaps the pandemic, since from this event emerged different studies on the role of digitization to mitigate the economic impact of a pandemic, Katz et al (2020) have generated empirical evidence indicating that the economic losses generated by Covid 19 in 2003 were significantly lower in those affected countries that had better provision of fixed broadband networks and better connectivity. Specifically, the study found that, after controlling for several variables, the countries affected by the health crisis that had fixed broadband penetration levels above 20% in 2003 did not suffer significant economic losses. On the other hand, affected economies with penetration levels below that threshold experienced an economic contraction, which was greater the lower the level of connectivity.

It is indisputable that in the most disadvantaged and less digitized territories, factors of change such as poverty to extreme poverty predominated, especially in Latin American countries, where there are high rates of unemployment, and the change of socioeconomic status for the majority of the population, there was a significant delay in education and in general the ordinary activities of the population (International Monetary Fund, 2021).

Regarding the Latin American and Caribbean region, all countries in the region reported cases and deaths, with the exception of Dominica and St. Kitts and Nevis. The region accumulated 18% of the total infections and 27% of the fatalities recorded in the world, considering that it concentrates 8% of the proportion of the world’s population. Cities and mega-urban areas are characterized by a number of deficiencies that constitute a significant risk of contracting COVID-19, such as overcrowding, lack of access to clean water, sanitation, electricity, internet services, as well as shortages and saturation in public transportation. Thus, the combination of a high degree of urbanization and significant deficiencies in health care and basic services influenced not only the magnitude and impact of the pandemic, but also the heterogeneous effect of the pandemic, resulting in the lowest income population being the most affected (Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean [ECLAC], 2021).

The consulted information on the productive performance of the region shows that between January and July there was a 6% increase in the trade of goods from the agriculture and fishing sectors, compared to the same period in the previous year; which contrasts with the 21% drop observed in other sectors. On the other hand, the products that have had the most significant negative impacts in the year-on-year comparison are: live animals (-40%), tobacco (-33%), prepared fruit and vegetable products (-18%), and cereals (-16%). On the other hand, the products that have had the greatest positive impact are: sugars and sweeteners (44%), oilseeds (33%), vegetables and tubers (25%), and milk and dairy products (17%) ((FAO and ECLAC, 2020)). Therefore, in order to strengthen trade in the region, it is critical to focus on the implementation of commercial promotion measures, whether taking advantage of the framework of trade agreements such as the WTO, or in response to crises such as the current one (UNCTAD, 2006; cited by FAO, 2021).

In the case of Mexico, regarding the impact on economic growth, a contraction of -5% was observed, related to an unprecedented fall in the US economy. On the other hand, the economy faced the crisis of stagnation (with a growth rate of -0.1% in 2019) and mediocre export performance (which fell by 0.6% in 2019-Q4). However, given the sharp decline in domestic consumption and investment, it is expected that exports will quickly become the engine of recovery (BID, 2020), depending on the pace of vaccination of the population and the economic recovery performance in the United States.

It is in this way that it is possible to observe that the actions that are being carried out both in Mexico and around the world, the process of adapting to a “new normal” scenario will represent a factor of fundamental importance for social coexistence considering the risk that the new coronavirus represents, and therefore, this transition process towards this new way of interacting is a focal point of public policies for the majority of governments on the planet.

The process of transitioning towards a new economic normality.

The world is adapting to a new normal in which healthcare and the economy are highly relevant in people’s lives. In the short term, strengthening public health systems, early detection, tracing of infections, ensuring space and equipment for the care of severely ill people should be as relevant as any public policy designed at the moment, given the serious trauma humanity has faced as a result of this pandemic (Wallentin, Kaziyeva and Reibersdorfer-Adelsberger, 2020).

As for businesses, the economic, technological, and reputational pressures of the present moment risk disorderly change, threatening to create a large cohort of workers and companies that are displaced from future market opportunities. Therefore, governments must balance managing the pandemic and economic contraction while simultaneously creating new opportunities for social cohesion and the viability of their populations. Long-term environmental risks that may coincide with social fragmentation due to changes in the planet’s dynamics may potentially hinder the ability of lawmakers and other leaders to act and resolve such issues (World Economic Forum, 2021), potentially generating new crises of social, political, and economic order.

Given this scenario, the Government of Mexico has announced a series of actions for continuity and orderly, gradual, and cautious reopening with the aim of continuing to take care of people’s health in the workplace while reactivating the economy through three stages: the determination of “Municipalities of Hope” (without reported SARS-CoV-2 infections or proximity to municipalities with infections) with the opening of all work, social, and educational activities; a second stage that consisted of expanding companies considered essential and issuing Technical Guidelines for Health Safety in the Workplace for the early reactivation of these sectors; and the third stage through a weekly epidemiological risk traffic light system by regions (state or municipal), which will determine the level of health alert and define what type of activities are authorized to be carried out in economic, labor, school, and social areas (DOF, 2020).

These considerations are emerging strategies adopted by the Mexican government to ensure adequate and, to some extent, risk-free interaction for the Mexican population. Therefore, Mexican society has begun a process of insertion into a model of capitalism that must weigh social, economic, environmental, and health dimensions equitably for the population through the design of a new model of capitalism.

The function of capitalism in a “new normal” dynamic

The modern industrial economy, such as capitalism, is possibly the largest socially constructed ecosystem today, shaping our entire way of life. As an ecosystem, the global economy self-organizes through learning, but it suffers from structural irreversibility and a tendency to slow down growth, leading to loss of continuity and uncertainty about the future (Filho et al., 2020).

In this way, the capitalist system of economic, cultural, scientific, and social exchange at the global level manifests itself through the generation of a power gap between “global cities” and rural areas. Global cities represent urban spatial agglomerations of capital, labor power, company, banks, infrastructure, corporate headquarters, service industry, international financial services, and telecommunication facilities. Such mega-cities include, for example, New York, London, Tokyo, Paris, Frankfurt, Zurich, Amsterdam, Los Angeles, Sydney, São Paulo, Mexico City, and Hong Kong. “The more global the economy becomes, the greater the agglomeration of central functions in relatively few places, namely global cities” (Sassen 1991, p:5, cited by Fuchs, 2020).

However, capitalism as currently conceived, oriented towards profitability through the exploitation of capital goods (in the case of free-trade capitalist countries), or through planning and state control over production goods (in the case of state capitalism), produces financial, human, and environmental crises. In that sense, the fundamentals of capitalism oriented towards profitability obtained by the exploitation of capital goods have been questioned as the main objective of business. In that sense, perhaps one of its main failures is that it has not generated adequate responses to some of humanity’s greatest problems, such as poverty, inequality, and environmental destruction. As a sign of this, for millions of people living in less privileged parts of the planet, the lockdown represented unemployment and hunger. Without income, basic food and access to health care, people live in a desperate situation (Caduff, 2020).

The radical rupture that COVID-19 has made evident requires an economic transformation oriented towards sustainable and inclusive development that can survive future shocks, whether new pandemics, climate change, financial instability, or conflict (Leach et al., 2021). Therefore, it is urgent to learn the key lessons from its economic consequences and to guide the debate on possible actions that can establish our societies on a more stable, healthy, equal, and sustainable development trajectory (Lucchese and Pianta, 2020).

Before the emergence of problems related to the crisis of the so-called “Great Lockdown,” success in the capitalist system was based on the accumulation of wealth and reinvestment in order to accumulate more money, based on an ideology where the end justifies the means, resulting in an unsustainable and devastatingly harmful utopia based on a senseless cycle where it is necessary to exchange goods (e.g. products, services, raw materials, property rights) to generate flows of money through that exchange. When this process breaks down, money stops flowing, people are laid off, debt interest is not paid, investments fail, companies go bankrupt, banks have problems, and savings are lost (Spash, 2020). Needless to say, it represents an unsustainable long-term model from various perspectives and is currently reflected in the worst human and economic crisis with hundreds of millions of people without jobs or means of livelihood, with an increase in gender inequality and extreme poverty levels (Oldekop et al., 2020).

This stage, characterized by economic slowdown and job losses, has exposed flaws in the implementation and development of stakeholder governance. With regards to the development of a scenario related to the “new normal” of post-COVID life, it is important to consider that a fundamental transformation is needed in corporations and companies at all levels, with a greater focus on social responsibility and transparency towards key stakeholders (Grove et al., 2020). That is to say, the political, economic, social, and health disruption caused by COVID-19 could, in theory, strengthen the momentum to adopt a long-term capitalism model with less emphasis on delivering value to shareholders and a greater focus on meeting the legitimate interests of stakeholders such as workers and the general community (Coulter, 2020).

Therefore, organizations such as the World Economic Forum have proposed that it is necessary to implement a new economic system, called “Stakeholder Capitalism” (WEF, 2020), because current times demand recognition that, in terms of contemporary capitalism as an economic system, the dominant means of production must enter a new era that requires methods of control, responsibility, and accountability, where companies (regardless of size, sector, public, private, or mixed) become authentic trustees of society (O’Brien, 2020), which can represent a vehicle for the redistribution of wealth and the opportunity to generate a shift in the focus of capitalism, from shareholders to a capitalism oriented towards the expectations and needs of stakeholders (Ashford et al., 2020).

A necessary economic model: Stakeholder capitalism as a response to current global challenges

According to Edward Freeman’s seminal work, stakeholder capitalism can be defined as an economic system that involves economic, environmental, social, and governance aspects with the aim of achieving a state of well-being for all stakeholders, thereby safeguarding the quality of life of future generations (Freeman et al., 2007); this seminal work can be interpreted as a managerial approach to organizations where stakeholders are being owed responsibility by the managerial agents (Hühn, 2023), thus becoming an essential part of the agency theory with a broader scope.

This form of economic system is distinct from “shareholder capitalism” oriented mainly towards maximizing profitability for capital goods, as well as from “state capitalism,” which is related to state intervention for a long-term planned, sustainable economy that is suitable for the real needs of current and future generations.

To distinguish the different economic systems derived from capitalism, various authors present three models that serve different objectives: Shareholder capitalism, State capitalism, and Stakeholder capitalism. In the case of shareholder capitalism, it is widely used by most Western corporations, where the main objective is represented by the pursuit of maximizing profits or, more generally, maximizing profitability for shareholders. On the other hand, state capitalism entrusts the government with the direction that the economy should follow and is a model mainly adopted in emerging markets, particularly in Asia (Schwab, 2019; cited by Mhlanga and Moloi, 2020).

With regard to stakeholder capitalism, it represents a “managerial capitalism for all stakeholders,” understood as a proposition of value creation about which value is generated by contributing resources to common objectives, resulting in a driver oriented towards transforming the business in turbulent environments (Windsor, 2009). In this way, stakeholder capitalism arises within companies and their interaction with relevant stakeholders, such as employees, customers, suppliers, competitors, government institutions, credit institutions, among others.

Thus, stakeholder capitalism is not only based on private property, self-interest, competition, and the free market, whose vision requires constant justification based on achieving good results or avoiding authoritarian alternatives. Freeman and other authors argue that an alternative is required where an economic system is based on freedom, rights, and the creation by consensus of positive obligations (Freeman et al., 2007), and in that sense, businesses will find more effective to invest in social institutions as a strategic approach to competitiveness, since this action could contribute to the enhancement of the environmental, financial, and economic context that allows organizations to produce goods, and distribute benefits more effectively (Owen & Kemp, 2023).

That is one major reason why it represents an essential activity for organizations to take into considerations how different domains of stakeholder capitalism could contribute to variable impacts, by focusing on different issues regarding workers, customers, communities, the environment, and owners (Goswami & Bhaduri, 2023).

To better understanding Khosla, & lder capitalism, some of the most relevant constructs of Stakeholder Theory must address to subjects such as stakeholder construct, stakeholder salience, corporate social responsibility, and value creation processes (Beck & Ferasso, 2023), and by building such theoretical understanding, managers will be able to link stakeholders needs and expectations to measuring relevant subjects, including metrics of the triple-bottom line: environmental, social, and governance (Jones‐Khosla, & Gomes, 2023).

It is in this way that the management of the expectations and needs of stakeholders allows a given company to respond to the contingencies presented by the environment to which it belongs, and in terms of the design of public policies, the adequate and necessary process of inserting Mexican SMEs into a stakeholder capitalism model, given that some of the main benefits that characterize this type of system are related to the pursuit of a better quality of life for the people involved.

It is important to note that stakeholder capitalism is not the only concept born out of the need to find a new system that adapts to the post-pandemic world. The concept has undergone an evolutionary process full of diverse changes that have had to be adjusted to global circumstances.

Several concepts of capitalism can be mentioned that have been born to give an answer to the conventional system or to give a solution to a particular problem. The Marxist version of capitalism focuses mainly on the opposing groups of labor and capital, fighting over the fixed resources of productive assets. Economic and business activity itself is amoral and the only inevitable solution for labor is to take control of those productive assets by force.

Another equally valid concept is government capitalism which was born around the same time as labor capitalism but which had a different vision since its author’s conception is about government intervention to repair the errors of the market.

Literature review

Regarding the construct related to the contribution to the planet by Mexican SMEs, access to certification processes in SMEs is significantly affected by the solvency and income levels that these types of organizations have in a given period. This also explains why sometimes these companies have practices related to ISO-9001 certification, in addition to corresponding certifications related to sustainability (INEGI, 2019). In this sense, quality certifications are relevant for the development of processes that meet the needs, expectations, and desires of the main stakeholders and are a factor that directly impacts the income, resilience, and competitiveness of organizations (Ayala et al., 2004; cited in Bárcenas et al., 2009).

On the other hand, in terms of the construct related to people management, one of the relevant aspects in the development of a company is the training and development of professional competencies in personnel with the objective of increasing the productivity of the social organism. Strengthening the professional competencies of workers has a significant effect on the increase in the income of companies since it represents an intangible asset of human capital, mainly in relation to the quality of the product or service (Fuentes et al, 2016).

Definition of constructs related to contribution to the planet, people management, orientation towards prosperity and governance factors in Mexican SMEs in a stakeholder capitalism. Regarding the construct related to the contribution to the planet by Mexican SMEs, access to certification processes in SMEs is significantly affected by their solvency and income levels in a given period, which also explains why these companies sometimes have practices related to ISO-9001 certification, in addition to corresponding certifications related to sustainability (INEGI, 2019). In this sense, quality certifications are relevant for the development of processes that meet the needs, expectations, and desires of the main stakeholders, and this is a factor that directly impacts the income, resilience, and competitiveness of organizations (Ayala et al., 2004; cited in Bárcenas et al., 2009).

On the other hand, in terms of the construct related to people management, one of the relevant aspects in the development of a company is the training and development of professional competencies in employees with the aim of increasing the productivity of the social organization. Strengthening employees’ professional competencies has a significant effect on the increase of companies’ income, as it represents an intangible asset of human capital, mainly in relation to the quality of the product or service (Fuentes et al, 2016).

Continuing with the set of constructs of interest, the one related to orientation towards prosperity is based on a set of characteristics related to economic growth, built under a scheme of decent employment, decent livelihood, social security, and health protection for the people who make up the internal stakeholders of the company (WEF, 2020). In addition to this, the management of the business in question with a solid orientation towards innovation is essential, considering that the investment made in innovation processes has been found in various studies to be a variable that offers significant positive effects on the growth and development of organizations that favor this type of investment (Jaffe et al., 2006; cited by Citlalli López-Torres et al., 2016) in terms of continuous improvement of products, processes, services, and, in general, in processes related to the management of the organization, such as the introduction of new organizational methods, new business practices, and new ways of managing external relations, in order to generate greater productivity and/or efficiency in achieving the organization’s objectives (OECD and Eurostat, 2018).

Finally, regarding governance factors, in terms of the role of different government institutions, due to the magnitude and importance of productive and formal SMEs, as well as entrepreneurs, public policies must function as an intentional strategic action oriented towards national development and its inhabitants, which is why it represents an important stakeholder group for companies that require resources such as investment, training, or integration into productive networks. As a way of achieving this objective, there are a series of supports aimed at promoting the development of entrepreneurial productive projects in Mexico, through agencies such as the Ministry of Economy, the Ministry of Social Development, the National Council of Science and Technology, the Ministry of Agrarian and Urban Development, and the Ministry of Agriculture, Livestock, Rural Development, Fisheries and Food, among others (SELA, 2015).

The review of the state of the art referred to in the articles included in the preceding table shows that the topics can be summarized in terms of stakeholder identification, relevance and management, strategy, corporate social responsibility, business intentions, and project management. The methodology to be used to answer the research question described in this paper is discussed next.

Referential framework: Most influential works related to stakeholder management

To have a better perspective of the works with the highest number of citations in the field of stakeholder management, according to the information obtained from the Scopus platform, the following 13 works with the greatest influence in the scientific field are listed below.

Table 1

Most influential articles on the topic of stakeholder management.

|

Autor(es) / Year |

Title / Source |

Affiliation |

Summary |

|

Mitchell et al., (1997) |

Toward a theory of stakeholder identification and salience: Defining the principle of who and what really counts (Academy of Management Review) |

University of Victoria; University of Pittsburgh. |

Contributes to the theory of stakeholder identification and importance, based on the determination of one or three relational attributes: power, legitimacy, and urgency, through a typology of stakeholders, propositions regarding the importance of the stakeholder for the company administrator. |

|

Orlitzky et al., (2003) |

Corporate social and financial performance: A meta-analysis (Organization Studies) |

AGSM, UNSW, University of Sydney, Dept. of Mgmt. and Organizations, University of Iowa. |

The presented research shows a meta-analysis of 52 studies (representing the population of a previous quantitative research) with a sample size of 33,878 observations, where the findings suggest that corporate virtue in the form of social responsibility, and to a lesser extent, corporate responsibility, is likely beneficial for companies. |

|

Carroll (1991) |

The pyramid of corporate social responsibility: Toward the moral management of organizational stakeholders (Business Horizons) |

University of Georgia, Athens. |

Explores the nature of corporate social responsibility (CSR) with a focus on understanding the parts that make it up. The intention is to characterize CSR in a way that is useful for executives seeking to reconcile the company’s obligations to shareholders with other groups that are legitimate for the organization. |

|

Wilkinson et al., (2016) |

Comment: The FAIR Guiding Principles for scientific data management and stewardship (Scientific Data) |

Center for Plant Biotechnology and Genomics et al** |

A diverse set of stakeholders (including academia, industry, funding agencies, and academic publishers) have worked together to design and endorse a concise and measurable set of principles referred to as “FAIR Data Principles”. The intention is for these principles to act as a guide for those seeking to strengthen the reuse of their data repositories. Unlike similar initiatives that focus on human scholarship, these principles place a specific emphasis on strengthening the ability of machines to automatically find and use data, in addition to promoting their reuse by individuals. |

|

Krueger et al., (2000) |

Competing models of entrepreneurial intentions (Journal of Business Venturing) |

Boise State University, Montana State University, University of California Los Angeles. |

Compares two intention-based models in terms of their ability to measure entrepreneurial intentions: Ajzen’s Theory of Planned Behavior and Shapero’s Entrepreneurial Event Model. A statistical fit test is conducted to determine how well the results support each component of the models. The study’s results argue that promoting entrepreneurial intentions by promoting public perceptions of feasibility and desirability is not only appropriate but relevant. |

|

Hillman y Keim (2001) |

Shareholder value, stakeholder management, and social issues: What’s the bottom line? (Strategic Management Journal) |

Ivey School of Business, University of Western Ontario, Ivey School of Business, University of Western Ontario |

The work demonstrates a test of the relationship between shareholder value, stakeholder management, and engagement in social issues, showing that building better relationships with stakeholders such as employees, customers, suppliers, and communities can increase shareholder wealth by supporting companies in developing valuable intangible assets that can be sources of competitive advantage, using data from the top 500 companies in the S&P index. The evidence further shows that stakeholder management leads to greater value for shareholders, while engagement in social issues is negatively associated with shareholder value. |

|

Burgstahler y Dichevm (1997) |

Earnings management to avoid earnings decreases and losses (Journal of Accounting and Economics) |

School of Business, University of Washington, School of Business Administration, University of Michigan. |

This work provides evidence that companies manage reported earnings to avoid decreases in profitability and losses. Specifically, in cross-distributions of changes in profitability, unusually low frequencies of small decreases in earnings and small losses, as well as small increases in profitability and small positive income, were found. From this, evidence is presented that two components of earnings and operating cash flow, as well as changes in working capital, are used to achieve increases in company profitability. |

|

Abrahamson (1996) |

Management fashion (Academy of Management Review) |

Columbia University; Stern School of Business, New York University; Mgmt. of Organizations Department, Columbia Business School |

This research urges academics to study the processes of establishing management systems, as well as to explain when and how they serve shareholders, employees, managers, students, and other stakeholders. Additionally, it suggests intervening in these processes to make them more technically useful as authentic processes of collective learning for these stakeholders. |

|

Buhalis (2000) |

Marketing the competitive destination of the future (Tourism Management) |

Department of Tourism, Univ. Westminster. |

This research explains the concept of tourism competitiveness and aims to synthesize various models for strategic marketing and management of tourism destinations. It provides general information on widely used techniques and illustrates examples from various parts of the world. Additionally, it explains that marketing of tourism destinations should balance the strategic objectives of all stakeholders as well as the sustainability of local resources. |

|

Berman et al., (1999) |

Does stakeholder orientation matter? The relationship between stakeholder management models and firm financial performance (Academy of Management Journal) |

Boston University, University of Washington. |

This research contributes to the development of stakeholder theory by deriving two distinct stakeholder management models from existing research, testing the descriptive accuracy of these models, and including important variables from the strategy literature in the tested models. The results provide support for a strategic stakeholder management model but do not support an intrinsic stakeholder engagement model. |

Note. Own elaboration using data from Scopus (2023)1.

As it is shown on table 1, an economic model based on engaging and attending needs and expectations from essential stakeholders must consider some aspects such as identifying relevant stakeholders and their salience, understanding their needs and expectations as a basis for designing a model that includes dimensions related to people, profits and sustainable practices that cares about the planer, reconciling the company´s obligations to shareholders (long term vision) with the legitimate groups that are relevant to the company (short and long term) promoting ethics in business by building better relationships with interest groups such as employees, customers, suppliers, and communities.

In that sense, the following sections of the present work will explain the methods, techniques and instruments used to verify the hypothesis of this research.

1. Methods, techniques, and instruments

The present work uses a descriptive quantitative and graphic analysis focused on positive economics (whit actual data that represents rational economics for the short term in a given period of time), that provides descriptive evidence about a proposal relative to normative economics (that could be irrational in the short term but rational in the long term, considering rationality the highest value at the lowest cost/price in the decisions of the company regarding their economic activities), to identify the process of allocation of resources performed by Mexican SMEs.

To do so, the paper will present a conceptual description that represents the participation of Mexican SMEs in what can be considered as a stakeholder capitalism model of the post-COVID19 era, using data obtained from the economic censuses generated by the National Institute of Statistics and Geography (INEGI). In this context, INEGI, INADEM, and the National Foreign Trade Bank (BANCOMEXT) jointly designed and generated the National Survey on Productivity and Competitiveness of Micro, Small, and Medium-sized Enterprises (ENAPROCE), which includes information related to the measurement of managerial skills and entrepreneurship, sources of financing, production chains, technological and innovation capacities, business environment, regulation, and knowledge of government support.

The strategic sectors corresponding to various dimensions related to stakeholder capitalism includes various constructs proposed by the World Economic Forum to measure indicators related to stakeholder capitalism, as shown in the next model of constructs and variables including Planet, People, Profit and Governance, as is shown in table 2.

Table 2

Constructs related to stakeholder capitalism, including Planet, People, Profit and Governance and the correspondent measurement variables according to INEGI

|

PLANET |

Number of companies that had some certification by strategic sectors |

PL1 |

|

Construction licenses, environmental impact or water usage (CONAGUA) |

PL2 |

|

|

PEOPLE |

Number of companies by gender of the decision-maker by strategic sectors (Man) |

PE1 |

|

Number of companies by gender of the decision-maker by strategic sectors (Woman) |

PE2 |

|

|

Average of dependent and independent employees of the legal entity that worked in companies according to gender (Women, Directives and supervisors) |

PE3 |

|

|

Average of dependent and independent employees of the legal entity that worked in companies according to gender (Women, Frontline) |

PE4 |

|

|

Average of dependent and independent employees of the legal entity that worked in companies according to gender (Men, Directives and supervisors) |

PE5 |

|

|

Average of dependent and independent employees of the legal entity that worked in companies according to gender (Men, Frontline) |

PE6 |

|

|

Average of dependent and independent employees of the legal entity that worked in companies according to level of education by strategic sectors (No instruction) |

PE7 |

|

|

Average of dependent and independent employees of the legal entity that worked in companies according to level of education by strategic sectors (Basic education) |

PE8 |

|

|

Average of dependent and independent employees of the legal entity that worked in companies according to level of education by strategic sectors (Highschool) |

PE9 |

|

|

Average of dependent and independent employees of the legal entity that worked in companies according to level of education by strategic sectors (High Education) |

PE10 |

|

|

Annual remuneration paid to dependent employees who worked in companies by strategic sectors |

PE11 |

|

|

Number of companies that provided training to staff using internal or external trainers by strategic sectors |

PE12 |

|

|

Occupied staff who were trained by companies according to gender and expenses incurred (Women) |

PE13 |

|

|

Occupied staff who were trained by companies according to gender and expenses incurred (Men) |

PE14 |

|

|

Spending (Millions of pesos) |

PE15 |

|

|

Number of companies according to the reason for performance bonuses for non-managers by strategic sectors |

PE16 |

|

|

Number of companies according to the characteristic on which performance bonuses for managers were based by strategic sectors (performance and skills) |

PE17 |

|

|

PROFIT |

Sales value of the three main products (goods or services) manufactured or offered by companies in strategic sectors |

PR1 |

|

Revenues obtained by companies in strategic sectors |

PR2 |

|

|

Amount of exports by companies in strategic sectors |

PR3 |

|

|

Number of companies according to their access to financing sources, as well as the amount received by strategic sectors (Developing financial institution) |

PR4 |

|

|

Number of companies according to the most important financing source according to the term by strategic sectors (Own resources) |

PR5 |

|

|

Number of companies according to the decision to take out a bank loan for the company under current average terms by strategic sectors Interest rate (%) |

PR6 |

|

|

Number of companies that participated through contracts or collaboration programs in productive chains |

PR7 |

|

|

Average age of the companies that began to participate in productive chains by strategic sectors |

PR8 |

|

|

Number of companies according to the link in the productive chain in which they are located (First level) |

PR9 |

|

|

Number of companies according to the link in the productive chain in which they are located (Second level) |

PR10 |

|

|

Number of companies according to the link in the productive chain in which they are located by strategic sectors Retail |

PR11 |

|

|

Number of companies according to the main benefit obtained by being integrated into productive chains by strategic sectors (Training and technical assistance |

PR12 |

|

|

Number of companies according to the main benefit obtained by being integrated into productive chains by strategic sectors (Credit history and access to other funding schemes) |

PR13 |

|

|

Number of companies according to the main benefit obtained by being integrated into productive chains by strategic sectors (Capabilities certification) |

PR14 |

|

|

Number of companies according to the main benefit obtained by being integrated into productive chains by strategic sectors (Access to other markets) |

PR15 |

|

|

Number of companies according to the main benefit obtained by being integrated into productive chains by strategic sectors (Improved management practices and planning) |

PR16 |

|

|

Number of companies according to the main benefit obtained by being integrated into productive chains by strategic sectors |

PR17 |

|

|

GOVERNANCE |

Number of companies that supply the government by strategic sectors (Contractor) |

GB1 |

|

Total expenses that companies incurred in a normal month to comply with their federal tax obligations by strategic sectors, |

GB2 |

|

|

Number of companies according to their knowledge of Federal Government programs for promotion and support for companies by strategic sectors |

GB3 |

|

|

Number of companies according to the application and support received from Federal Government programs according to the amount granted by strategic sectors |

GB4 |

|

|

Problems with public safety |

GB5 |

|

|

Competition of informal companies |

GB6 |

|

|

Excesive government procedures |

GB7 |

|

|

Number of companies according to the main procedure to which they devote the most time and resources and which they consider an obstacle to their growth by strategic sectors: Procedures or permits related to the constitution of the company |

GB8 |

Note. Own elaboration based on INEGI (2019).

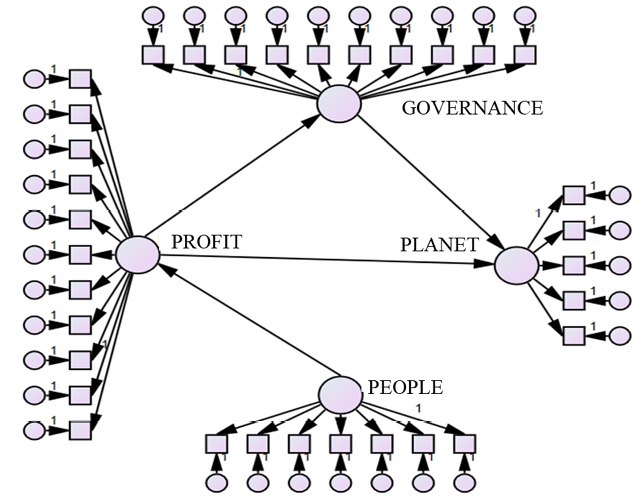

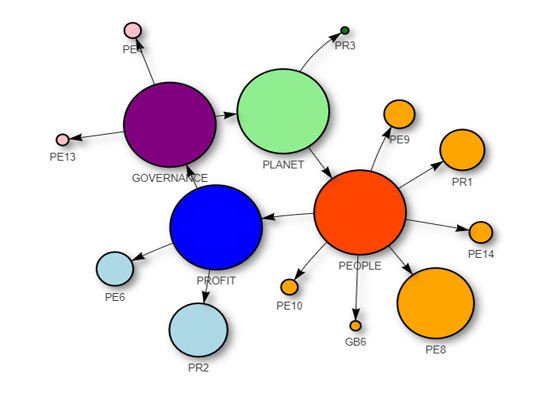

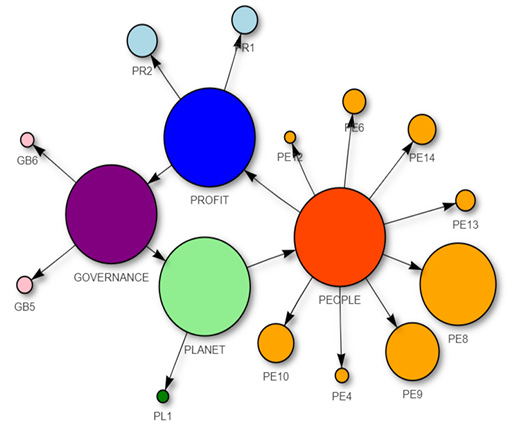

With the information previously described, the theoretical-conceptual, descriptive network model is presented, through which a relationship is established between constructs and the empiric variables that represents how the Mexican SME´s are behaving in terms of stakeholder capitalism; essentially, this model will be later represented using the database of INEGI as basis, presenting the overall contribution of each sector of the economy (manufacturing, trade and services) to the planet, people management, prosperity orientation, and governance factors as is presented below in the Figure 1:

Figure 1

Hypothetical model representing constructs related to contribution to the planet, people management, prosperity orientation, and governance factors that explain the participation of Mexican SMEs in stakeholder capitalism.

Note: Own ellaboration (2023).

It is important to note that each construct is formed by a series of empirical variables, that are referred to in table 2, and thus, this is a graphic representation of each element that is considered in a stakeholder capitalism model.

Based on the figure 1, the sections related to results and discussion present the descriptive analysis using empirical data from INEGI for each element included in the proposal model, helping to understand graphically a contrast analysis in each great sector of the Mexican economy, including Manufacture, trade and services.

2. Results and discussion

Firstly, the descriptive analysis of the variables included in the model, considering the data obtain from INEGI, the most common empirical variables that are part of the general environment of Mexican SMEs are represented in the following table 3, considering the 3 great sectors of the economy; it is relevant to highlight that some of them represents part of the managerial procedures of the company, in relation to employee management practices, gender, and level of sales; additionally, the table presents some of the most important issues and concerns for these organizations, such as public safety and informal companies, as follows.

Table 3

Variables that are most relevant to the combination of factors that represents the contribution of in each great sector to a stakeholder capitalism model.

|

Empirical variable |

Manufacture |

Trade |

Services |

|

Average of dependent and independent employees of the legal entity that worked in companies according to level of education by strategic sectors (Basic education) |

X |

X |

X |

|

Revenues obtained by companies in strategic sectors |

X |

X |

X |

|

Sales value of the three main products (goods or services) manufactured or offered by companies in strategic sectors |

X |

X |

X |

|

Average of dependent and independent employees of the legal entity that worked in companies according to gender (Men, Frontline) |

X |

X |

X |

|

Average of dependent and independent employees of the legal entity that worked in companies according to level of education by strategic sectors (Highschool) |

X |

X |

X |

|

Occupied staff who were trained by companies according to gender and expenses incurred (Men) |

X |

X |

X |

|

Average of dependent and independent employees of the legal entity that worked in companies according to level of education by strategic sectors (High Education) |

X |

X |

X |

|

Average of dependent and independent employees of the legal entity that worked in companies according to gender (Women, Frontline) |

X |

-- |

X |

|

Occupied staff who were trained by companies according to gender and expenses incurred (Women) |

X |

-- |

X |

|

Competition of informal companies |

X |

X |

-- |

|

Problems with public safety |

-- |

X |

X |

|

Number of companies that had some certification by strategic sectors |

-- |

X |

-- |

Note. Own elaboration based on INEGI (2019).

As table 3 shows, the SMEs of the three great sectors of the economy shares the same empirical variables as the most commons issues in what in comes to management; there is only differences in relation to the average of dependent and independent frontline women employees (present in manufacture and services), the occupied female staff who were trained by companies (present in manufacture and services), competition of informal companies (present in manufacture and trade), problems with public safety (present in trade and services), and certifications (present in trade), that are considered as the most important issues in terms of managerial concerns for the companies included in the survey.

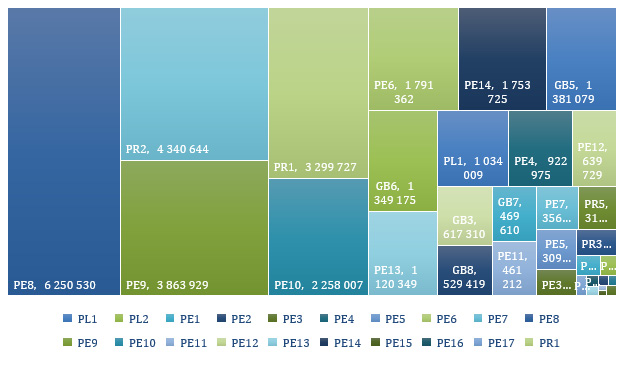

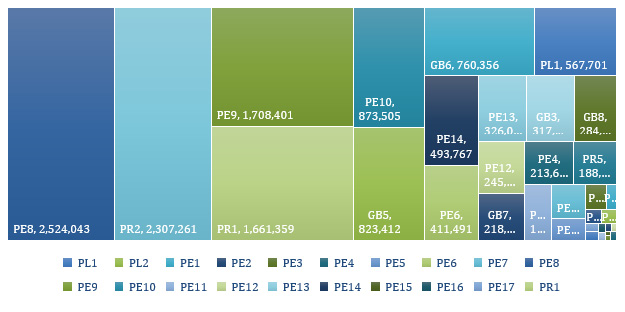

The next analysis is graphical and descriptive, representing the structure of the great sectors in terms of the managerial issues that represent the most important concerns for managers; in that sense, the next figure presents the graphical analysis of all the sectors combined, as follows.

Figure 2

Managerial structure representing the most relevant issues for managers for Mexican SME in all great sectors, including the empirical variable and the number of companies sharing such concerns.

Note. Own elaboration based on INEGI (2019).

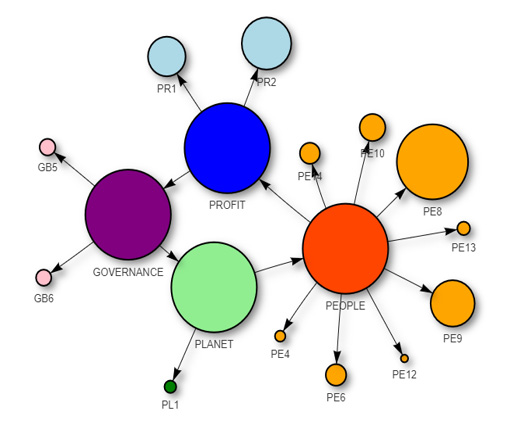

As it can be observed in figure 2, the five most important concerns for all the sectors combined include the average of dependent and independent employees of the legal entity that worked in companies according to level of education by strategic sectors (Basic education), the average of dependent and independent employees of the legal entity that worked in companies according to level of education by strategic sectors (Highschool), the revenues obtained by companies, the sales value of the three main products (goods or services) manufactured or offered by companies in strategic sectors and the average of dependent and independent employees of the legal entity that worked in companies according to level of education by strategic sectors (High Education); using this data, the network structure that represents the stakeholder management model of those companies in all three great sectors of the economy is represented in the next figure 3; the size of each node in the structure represents the relative proportion to the empirical variable that is the most common factor present in all the Mexican SME, as follows:

Figure 3

Managerial structure representing the aggregated empirical variables with constructs for all the companies in the Mexican economy

Note. Own elaboration using R Core Team (2020).

As the figure 3 shows, the variables related to management of people represents the most important stakeholder capitalism element for Mexican SMEs considering an aggregate network for all three great sectors of the Mexican economy, the factors related to profit and governance come next, and the part of the caring about the planet only includes one variable as the most common factor in that dimension, which is basically related to the certifications that the SMEs hold for their operations.

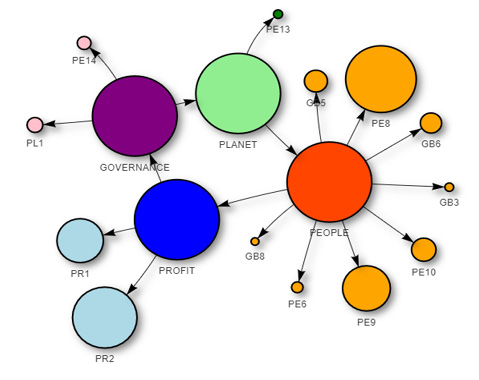

In the same sense, a disaggregated model is presented in the following graphics, considering the manufacture sector in the first place, where is possible to observe that the dimensions related to people and profit are the most common issues for management, as it is represented in figure 3.

Figure 4

Managerial structure representing the most relevant issues for managers for Mexican SME in manufacture sector, including the empirical variable and the number of companies sharing such concerns.

Note: Own elaboration based on INEGI (2019).

Figure 4 shows that the most relevant empirical variables for managers in a stakeholder capitalism model are related to the average of dependent and independent employees with a basic education and Highschool, sales value of the three main products, and average of dependent and independent men employees, meanwhile factors related to governance falls to the number 9 of relevance in this structure; this distribution can be also described as a interactive network among elements, that is represented in the figure 5 as follows.

Figure 5

Managerial structure representing the aggregated empirical variables with constructs for manufacturing companies in the Mexican economy.

Note: Own elaboration using R Core Team (2020).

The previous figure shows that the factor related to people is also the most relevant for this sector in a descriptive model for stakeholder capitalism, which is also consistent with the overall aggregated structure for all the 3 great sectors; in that sense, the following graphical analysis represents the trade sector, as follows.

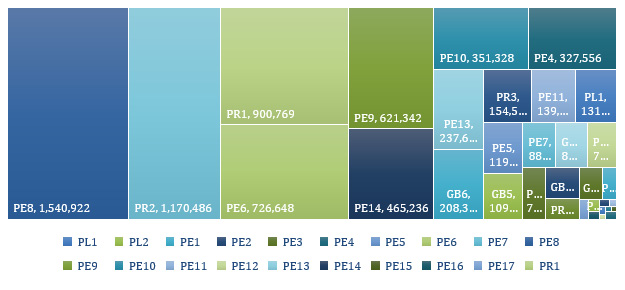

Figure 6

Managerial structure representing the most relevant issues for managers for Mexican SME in trade sector, including the empirical variable and the number of companies sharing such concerns.

Note. Own elaboration based on INEGI (2019).

As figure 6 shows, the most relevant factors in consideration for this sector are represented by Average of dependent and independent employees of the legal entity that worked in companies according to level of education by strategic sectors (Basic education and Highschool), Sales value of the three main products (goods or services) manufactured or offered by companies in strategic sectors and Revenues obtained by companies in strategic sectors, as the empirical variables that are most representatives; in that sense, This descriptive analysis can be represented as a network showing the descriptive interaction among factors related to stakeholder capitalism in a disaggregated analysis for the trade sector as follows.

Figure 7

Managerial structure representing the aggregated empirical variables with constructs for trade companies in the Mexican economy.

Note. Own elaboration using R Core Team (2020).

As it can be seen in the figure 7, the stakeholder model is consistent, having some differences with the previous structure for manufacturing companies in the element related to governance, given the fact that the distribution of variables for this model is more relevant in terms of the empirical variable of the number of companies according to the main procedure to which they devote the most time and resources and which they consider an obstacle to their growth by strategic sectors: Procedures or permits related to the constitution of the company, compared to other concerns to management.

Nevertheless, the structure remains a useful tool to describe graphically the constitution of stakeholder capitalism since the most important concerns for management remains practically in the same variables mainly in what it comes to the data related to people; finally, the next figure includes the data related to the service sector, as follows.

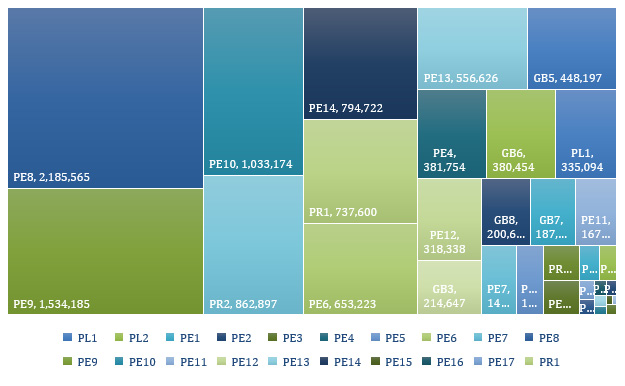

Figure 8

Managerial structure representing the most relevant issues for managers for Mexican SME in service sector, including the empirical variable and the number of companies sharing such concerns.

Note. Own elaboration based on INEGI (2019).

Figure 8 shows that the most relevant variables for the Mexican service sector are represented by the following aspects noticeable related to education: Average of dependent and independent employees of the legal entity that worked in companies according to level of education by strategic sectors (Basic education), Average of dependent and independent employees of the legal entity that worked in companies according to level of education by strategic sectors (Highschool) and Average of dependent and independent employees of the legal entity that worked in companies according to level of education by strategic sectors (High Education); also, a variable related to training represents an important element for this organizations, mostly in what it comes for the numbers related to occupied staff who were trained by companies according to gender and expenses incurred, in this case, for men working in these companies. The representation of the descriptive disaggregated analysis network of the figure 9 can be represented as follows.

Figure 8

Managerial structure representing the aggregated empirical variables with constructs for manufacturing companies in the Mexican economy.

Note. Own elaboration using R Core Team (2020).

Finally, figure 9 shows that even if the stakeholder model has some differences with the previous structure for manufacturing companies in the element related to governance, the network representation remains consistent to the description of the stakeholder capitalism approach to economy.

3. Conclusion

As seen in the results section the variable economy shares the same empirical variables as the most commons issues in what in comes to management; only significant differences appear in relation with the gender of the employees and the concentration of certain companies on hiring certain gender for certain activities, also another thing that changes is the competition of informal companies, problems with public safety, and certifications, that are considered as the most important issues in terms of managerial concerns for the companies.

This model shows that the process of adaptation to a “new normal” scenario will be a factor of fundamental importance for social coexistence, considering the risk represented by the effects caused by the new coronavirus, through the development of emergent strategies characterized by fostering appropriate interaction among stakeholders that make up a model of capitalism that must weigh the social, economic, environmental, and health dimensions equitably for the population.

With this conceptual definition, stakeholder capitalism will not only be based on competition for private property, self-interest, competition, and free markets, whose vision requires constant justification based on achieving good results or avoiding authoritarian alternatives, but in terms of public policy design, it will foster the appropriate and necessary process of integrating Mexican SMEs into a stakeholder capitalism model, since some of the main benefits that characterize this type of system are related to the pursuit of a better quality of life for the people involved.

The theory of stakeholder capitalism has a logical approach, since by allowing responsibility to be shared among the actors that make up the company, the common good will be sought above all interests. Actions such as these, especially in Latin American countries, will create a proactive change and change the current dynamics in a way that can promote a significant difference in both the way of life and the way of doing business.

The search for adaptation to a new model or the sole consideration of continuous improvement is indispensable for resilience. The creation of value from actors involved in all processes will generate a positive synergy in the companies.

In conclusion, ethical principles in economic activity, based on the principles proposed in the existing literature, are reaffirmed by consistency, whereby value can be created, exchanged, and sustained because stakeholders can jointly satisfy their needs and desires by making voluntary agreements with each other.

Notas